As sexual outlaws (and thereby sexual outcasts) Queers have a unique perspective on sexual ethics, one that stands outside mainstream cultural norms. As “resisting readers,” the Queer interpreters in this collection have used this perspective to generate new, creative, pro-Queer readings of biblical texts. This collection of articles goes beyond defensive treatments of “texts of terror” used by homophobic Christians to justify the oppression of Queers. The articles engage the reader in issues that challenge the contemporary Queer population.

For instance, in “A Love as Fierce as Death: Reclaiming the Song of Songs for Queer Lovers,” Christopher King sees a direct challenge to the “regimes of control (e.g., repressive laws and customs, shame-inducing mores) put into place by those whose interests Queers threaten.” King’s analysis of the Song of Songs exposes “the custodians of the social economy” who enforce “public fictions of purity, property and filial duty” by accusations of promiscuity, by verbal abuse, and by public violence. The Song of Songs erotic language and subject matter, argues King, upholds embodied human Eros as a genuine good, whose true measure is, “only the capacity to bring joy to the hearts” of lovers, and that it need “not conform to some external standard of “nature.” King’s reading of the Song includes the following conclusions: the sexual outlaw is a preferred object of loving desire and sexual interest; beauty alone is a sufficient motive for love, desire, and sexual union; all persons have the right to love as they will according to the dictates of reciprocal desire, equality, and intimacy. King’s careful textual reading and critical analysis make this article one of the most engaging in the collection.

“Perhaps the most revolutionary contribution of this volume is in its presentation of new and resistant practices of reading the Bible that challenge some of the prevailing “authorized” patterns of reading that allow the Bible to “clobber” oppressed people…If lesbians, gay men, bisexuals, transgender, and seeking people are to take back this word for themselves, they must take it back in a new way.”

~ Dr. Mary Ann Tolbert, George H. Atkinson Professor of Biblical studies and Executive Director, Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies in Religion and Ministry, Pacific School of Religion.”

Ken Stone’s, “The Garden of Eden and the Heterosexual Contract,” offers another powerful interpretation. It displays an extremely helpful methodological analysis and challenges our deepest notions of gender: the male/female dichotomy. Stone’s article presents a challenge to my incredulous reaction, many years ago, at reading French feminist deconstructionist claims that gender is a social construct. Indeed, Stone quotes Monique Wittig to argue that the “the categories “man” and “woman” are not neutral but dangerously “political” cultural constructs the “foundation upon which the heterosexualization of society” rest. Stone recognizes “that many cultures and societies (including those that produced the Bible) have valorized the sexual relation between women and men, especially in terms of its reproductive potential, and have stigmatized to varying degree other forms of sexual contact.” His interpretive strategy, then, is to de-stabilize this valorization found in the biblical creation stories and in “normative” and some “feminist” interpretations of these stories. For me, one of Stone’s most insightful observations is that “curse” placed on Eve for eating the forbidden fruit in the garden (that woman’s desire would be for a man) assumes female heterosexual attraction to men is an un-natural consequence of punishment for disobedience to God.

Celena M. Duncan’s observations in “The Book of Ruth: On Boundaries, Love and Truth” also challenge culturally-constructed categories of sexual desire. She proposes the book of Ruth demonstrates that “biodiversity and sexual diversity are God’s created norms.” Her analysis asserts that the commitment Ruth makes to Naomi, her mother-in-law, not only crosses ethnic and patriarchal boundaries, but creates a deep partnership with her. The words, “wherever you go, I will go; where you lodge, I will lodge. Your people become my people; your God is now my God. Where you die, I shall die and be buried,” have been and continue to be recited in the sacred rites of union, “marriages” and/or “commitment ceremonies” of thousands of lesbians. When Naomi sends Ruth to Boaz, the three of them constitute a bisexual family. While Duncan does not display the clear and careful textual analysis found elsewhere in this collection, she does clearly expose Queer use of homophobic rhetoric (“it’s a choice,” “it’s not natural,”) to reject and marginalize bisexuals.

“This readable volume assembles insightful and edgy biblical scholars who critically challenge long held assumptions that the Bible is not for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people.”

Chris Glaser, Author, Coming Out as Sacrament and The Word is Out: Daily Reflections on the Bible for Lesbians and Gay Men.

Victoria S. Kolakowski’s “Throwing a Party: Patriarchy, Gender, and the Death of Jezebel” contains a similar expose of Queer rejection of transsexuals. Kolakowski parallels the eunuchs in II Kings 9:30-37 with male-to-female transsexuals. She respectfully exposes the merits and deficiencies in both Nancy Wilson (lesbian author and UFMCC pastor) and Janice Raymond’s (lesbian separatist and Mary Daly’s partner) interpretations of eunuchs. Wilson and Raymond each establish the role of eunuchs as spies and infiltrators in enemy territory, each with a different master: a loving God versus a cruel patriarch. Wilson claims the eunuchs in this story who obey the king by throwing Jezebel out the window to her death, are “palace double agents of God and the prophet Elijah.” Raymond claims “there is a long tradition of eunuchs who were used by rulers, heads of states, and magistrates as keepers of women.” Fearing that every lesbian-feminist space will “become a harem,” she sees a patriarchal plot to control and contain the women’s movement by an infiltration of “transsexually constructed lesbian-feminists.” These transsexuals cannot be considered “un-men” just because they are castrated and “have acquired artifacts of a woman’s body and spirit.” I find such feminist-lesbian separatist rhetoric unconscionable, as it ignores or dismisses the agony suffered by transsexuals who struggle with inhabiting alien physical bodies. However, I appreciate Kolakowski’s respectful treatment of this perspective, because it gave me a deeper insight into the distrust, rejection, and lateral oppression I have seen aimed at lesbian-identified male-to-female transsexuals.

Ironically, the lateral oppression of bisexual and transsexual Queers by the gay and lesbian mainstream ultimately finds its support in a uniform and unquestioned acceptance of the culturally constructed concepts of gender dichotomy which underlie heterosexism. A total of eight articles in this collection address this issue which is so divisive in the Queer population.

Another divisive issue among Queers is the pressure for public revelation of one’s sexual orientation or “universal outness.” Six of the twenty-one articles in this collection address and valorize coming-out as normative. Only one defends remaining closeted in dangerous situations, “passing,” as a subversive strategy of resistance.

“This is an exhilarating, challenging, moving, and profoundly hopeful book. Anyone who would understand how the Bible speaks today needs to read this volume and listen hard to its prophetic voices.”

~ David M. Gunn A. A, Bradford Professor of Religion, Texas Christian University

Rebecca T. Alpert (“Do Justice, Love Mercy, Walk Humbly: Reflections on Micah and Gay Ethics”) sees coming-out as a prerequisite to walking with God. She argues there is “no holy way for a lesbian to be closeted to herself,” and that the “ultimate way to walk with God requires coming-out publicly.” She considers the “conspiracy of silence” created by closeted Jewish lesbians a “burden placed upon open lesbians by our closeted friends, to the detriment of lesbian life.” However, this “burden” should be born in humility and respect for those uncomfortable with their own sexuality or with their family. Irene S. Travis (“Love Your Mother: A Lesbian Womanist Reading of Scripture”) describes living in the closet as something of the past: “This was another way that the soul was murdered, choked to death by the lack of fresh air in the closet. . . a miserable way to live and a terrible way to die.”

Michael Piazza (“Nehemiah as a Queer Model for Servant Leadership”) pictures Nehemiah as an exile from Israel, probably a eunuch, and the cub-bearer to Persian King Artaxerxes living in the comfort, security and luxury of the royal palace. In this story, Nehemiah risked his security and privilege by asking the King to send him to the broken city of Jerusalem to rebuild it. Piazza unfavorably compares Nehemiah to “modern queer people who have risen to positions of power and influence but have remained closeted. Many of those people have even worked against their own people.” Mona West (“Outsiders, Aliens, and Boundary Crossers: A Queer Reading of the Hebrew Exodus”) severely criticizes Queer closeting and passing. She claims that closets “isolate, enslave and eventually kill us physically as well as spiritually.” Even while recognizing the legitimate fears and dangers of coming-out, she asserts passing is dangerous for both the Queer individual and the Queer community.

This closeted experience produces death, not only death to the existence of a queer community but also death to the individual. Maintaining a dual identity kills many. Queers die through the crushing of their spirits and the splintering of their wholeness. Queers die through addictions and often at their own hands when the only way out of the closet is suicide.

Finally, Benjamin Perkins (“Coming Out, Lazarus’s and Ours: Queer Reflections of a Psychospiritual, Political Journey) mediates the norm of “universal outness” by emphasizing that coming-out is far from an individual event; it must take place in community” (one that is loving and supportive of the process). I consider the above discussions dangerous and unreasonably coercive. They use not only the Bible, but theological, emotional and spiritual appeals to pressure Queers toward universal outness.

In opposition to interpretations which demonize closeted and passing Queers, Virginia Ramey Mollencott argues that public coming-out is neither a virtue nor an option available to all Queers. Mollencott honors passing as a necessary subversive strategy in what she calls “occupied territory.

Those who find themselves disadvantaged, on the outside, in the margins as it were, make use of trickery and other forms of manipulative behavior (like gossip, misinformation, nagging, playing possum, distractions and deceptions) because they do not have what sociologists refer to as assigned power. Assigned (usually to the elite in favor of the elite), but masquerading as divinely ordained, cosmically correct and unquestionably true – in short, an unassailable given.

Mollencott encourages Queers not to judge passing and valorize universal outness, but to remember and support “people in the often painful and messy realities of their lives.”

Each of the articles in this collection aims to promote justice for Queers through fresh biblical interpretations and creative reading strategies. Such strategies include the need to read with suspicion and the freedom to accept only what is healing in biblical texts with an invitation reject and/or laugh at the ridiculous claims of some texts. Each author acknowledges the social location of the reader as an inevitable and valid perspective. Those thirsty for biblical interpretations supporting their gender and sexual orientation will find a fresh stream here. Those who drink at this stream regularly, devotionally, will find delightful ways to mine new gold. This review only hints at the insightful, imaginative and diverse collection of articles included. As in all collections of this kind, some articles are stronger than others. However, even for those who hate, reject or ignore the Bible, this collection will not fail to engage the sophisticated reader in issues vital to the health and cohesion of the Queer population.

Book Description by Judith K. Applegate

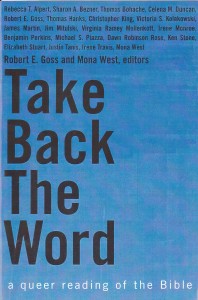

Paperback: 239 pages

Publisher: The Pilgrim Press (November 2000)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0829813977

ISBN-13: 978-0829813975

Product Dimensions: 0.7 x 5.9 x 8.9 inches